What if the Cuban missile crisis had gone badly? —Karl Young

I’M CONFIDENT human society would have survived, which I assume is your main concern. Even if things had gone off the rails, and the odd nuke popped off here and there, I think cooler heads would soon have prevailed.

But that’s easy to say now. For a week in October 1962 the whole planet was wondering if Cold War antagonism was about to boil over into nuclear armageddon.

Everyone knows the story: U.S. spy-plane photos reveal Russian nuclear-missile bases under construction in Cuba; Kennedy orders a blockade of the island and demands the missiles’ removal; six tense days later, Khrushchev complies. What’s better understood now is how little Khrushchev had thought through the ways it might all play out. He needed more negotiating leverage than the USSR’s iffy intercontinental missiles could buy him, and he hoped he could rattle the Americans by placing medium-range missiles at their doorstep.

The Americans were rattled all right. Despite the insistence of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara that the new deployment didn’t change the balance of power, the Joint Chiefs of Staff initially supported some sort of invasion of Cuba in response; it was only after a full week of deliberation that Kennedy was able to sell the blockade idea instead.

Why didn’t it go worse? Most obviously, neither side was crazy enough to want to precipitate the end of the world; it was pretty obviously acknowledged by both that detonating a nuclear bomb would be a bummer for all involved.

This was particularly plain to the Soviets in 1962, when the U.S. warhead stockpile was nine times the size of theirs. (They’d catch up over the next 15 years, and by 1978 were out in front.)

It was openly known by both governments that even if Russia were to launch all its missiles in Cuba, it couldn’t take out the U.S.’s capability to obliterate the USSR in response. So while theoretically we might have suffered massive loss of life, the chances of the Soviets purposely ordering the all-out attack needed to accomplish it were low.

Beyond that, historically speaking there simply haven’t been many preemptive wars—i.e., ones where, amid high international tension, one country strikes first for fear of becoming a target itself. By this standard, arguably the only cases since 1861 that qualify would be World War I, the Korean War, and the Arab-Israeli war of 1967. Empirically it seems difficult for governments to pull the trigger (so to speak), even when they’re under serious threat.

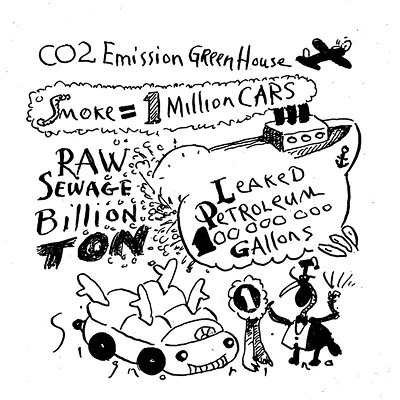

Nonetheless, it was a scary time, with many opportunities for the shit to hit the fan. During the last days of the standoff, sixty-plus B-52 bombers were in the air carrying nuclear payloads at any given time; one technical or communications glitch could have meant catastrophe.

A Russian submarine lost communication with the surface, assumed war had broken out, and almost launched its own nuclear torpedo. According to an Air Force vet who’s only recently come forward, at one point launch orders were sent by mistake to U.S. missile bases at Okinawa. The crews didn’t comply only because a commanding officer noticed enough irregularities in protocol to investigate further.

So let’s say the worst happened: an overconfident officer made the wrong call, or Kennedy listened to his military advisors. If the U.S. had invaded, we might have walked into another embarrassing Bay of Pigs-type fiasco—the Soviets had four times as many troops on the ground as the CIA thought at the time—but most likely no mushroom clouds.

If either side did go nuclear, though, accidentally or not, then we’ve got a whole different picture. The emergency document called the Single Integrated Operational Plan provided the U.S. military command with a prioritized list of thousands of targets in the Soviet bloc and China. The first tier of targets included missile launch sites, airfields for bombers, and submarine tenders; Cuba had all of these, making it an obvious place for an early attack.

Again, if the Soviets had struck first it’s likely the U.S. would have been able to retaliate, but that’s little consolation. U.S. antiballistic missiles developed under the (pre-sportswear) Nike program had proved largely useless in testing. Despite optimistic government-produced PSAs instructing citizens on how to wash radioactive particles off their potatoes, our country’s population would have been immediately reduced by 20 percent if a third of Soviet nukes had hit their targets.

If all of them had hit home, half the population would’ve been wiped out, not including after-the-fact deaths from fallout, starvation, etc. Of course, our retaliatory capability meant things would have been still grimmer on the Soviet end.

That said, it’s unlikely either side would have launched its full arsenal. A few tactical bombs might have gone off; there might have been a ground war in Berlin; possibly there’d be several million fewer people around now. But rationality won the day: it was in neither state’s interest to escalate.

This, unfortunately, may not hold true for today’s conflicts—but that’s another topic for another column.