SINCE THE early 1970s, author and artist Rosemary Wells has helped children navigate the world with her accessible stories and adorable illustrations:

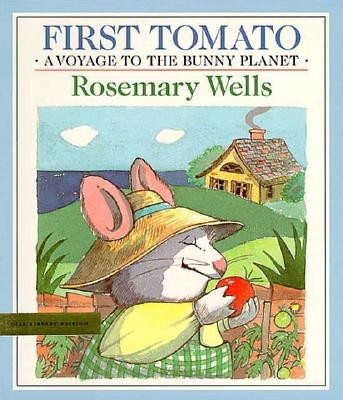

We learned how to get along with Benjamin & Tulip and how to get attention with Noisy Nora. A sweet kitten named Yoko showed us that being different isn’t so bad, and a Voyage to the Bunny Planet taught us how to make a bad day better.

Wells has penned and painted more than 100 other titles, and many of those ‘70s kids grew up to read their favorites to their own little bunnies.

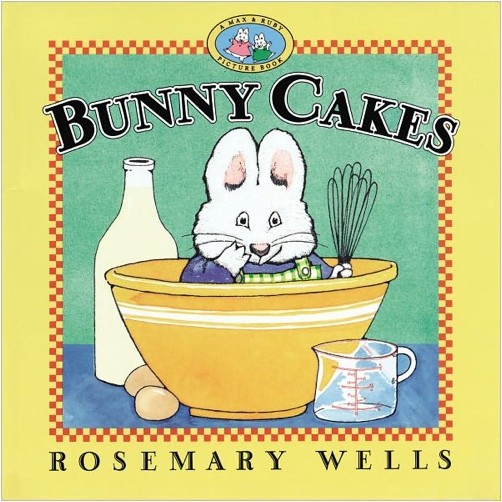

Now a grandmother of five, she may be best known for the 40+ books of the Max & Ruby series, the hilarious adventures of an exasperating little brother and his bossy big sis that have spawned a popular T.V. show. In recent years, she has branched into young adult fiction with On the Blue Comet and the Civil War-era historical novel, Red Moon at Sharpsburg.

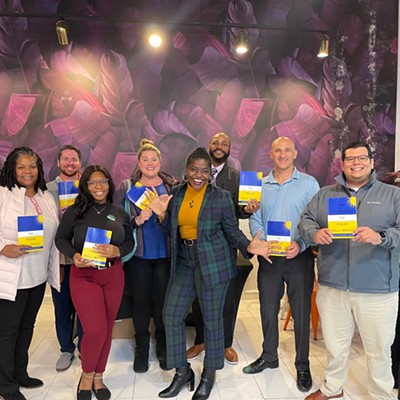

Wells joins other celebrity storytellers Lois Lowry (The Giver), Tedd Arnold (Rat Life, Hi! Fly Guy) and more than 50 other award-winning authors at Live Oak Public Libraries’ Children’s Book Festival this Saturday, Nov. 15 in Forsyth Park.

Jolly and as likable as one of her twinkly-eyed animal characters, she spoke to Connect from her home in upstate New York about limiting screen time, the evils of mandatory testing and how to find the Bunny Planet.

How has your work changed in the 46 years you’ve been writing for children?

Rosemary Wells: When I began, children’s book publishing was very different. It was still in the be-all, end-all realm of the librarians. They ran the whole marketplace.

Librarians were the ones who gave the reviews, they were the ones who bought for the libraries. They were educated and lovely and not commercially-minded at all. It was the great flowering golden age for children’s book publishing.

It was a quieter time—we still had busy signals! Editors and publishers didn’t have to attend meetings with the sales department all day like they do now. Which in my opinion is a pretty bad development for publishing, since people in the sales department tend to be 23 year-old chipmunks who know nothing.

In the 1970s, independent bookstores began becoming powerful, and technology allowed for four-color printing, which allowed artists to express their work in highly-detailed, beautiful ways. That lasted 20, 25 years and it was glorious—the libraries had money, the bookstores thrived.

Then it changed with the rise of chain bookstores and then Amazon, which totally paralyzed the independents. That was the end of the golden age of picture books, because the chains only wanted the television-oriented stuff they knew they could sell. Then the recession to took rest of the stuffing out of publishing.

It’s sad. Editorial should stand firm and stand alone. Unless you have that, it’s no longer literature. It’s just commercial product.

Has your artistic process changed with the advent of computers?

RW: I don’t use computers. And I must say I would never use the word “process!” It’s such a Cuisinart word, so mechanical, so formal. Sort of deadens what happens.

It’s a very gossamer thing; to call it a “process” doesn’t do it justice. Some things are a process, like taxidermy or cooking. But those are skills that can be acquired. No one can train a writer or an artist. What works, works.

Me, I have something like a sieve in my head, and once in a while something gets stuck. If it stays there long enough, it will become a book. Books have a life of their own, separate from me. Some choose to land at my airport. That’s all I can say.

Can you explain the practice of précis writing and how it influenced you?

RW: Every Monday my junior year of high school, my English teacher gave us a 50-word paragraph and told us to reduce it by five words at a time until Friday—without losing any meaning. From this I learned to be direct and concise. It was wonderful training for a writer.

I always write before I draw. Obviously, since the word “illustrate” means to illuminate an existing text. Then I cut down and cut down the text and put together a dummy for my publisher.

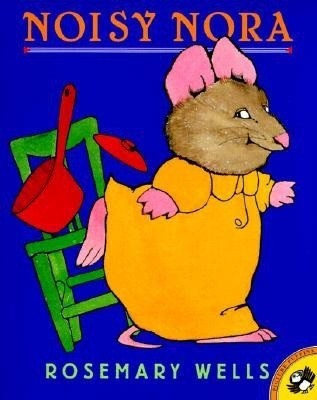

Who was the inspiration behind Noisy Nora?

RW: My best friend was a middle child of four and very noisy. This family order amazed me since I was an only.

Who did Max grow up to become?

RW:Currently Max is raising funds to create the first wind farm in Tompkins County, New York. She also runs a green roof plant company called Mother Plants with a 50-acre farm and teaches horticulture courses at Cornell. She has two kids.

Can you give directions to the Bunny Planet?

RW: Each of us has different pathways to the Bunny Planet.

Forgive me for being such a fangirl; I grew up on your books and read them to my kids! You and Judy Blume had a tremendous influence on me.

RW: Oh, Judy’s a great friend of mine.

OK, now I’m freaking out. What do you talk about when you get together?

RW: Well, we don’t talk about books. We talk about husbands and grandkids. And lunch!

Are you a fan of reading on iPads and tablets?

RW:Technology comes to all of us, untested and often unwanted. It just appears like summer mushrooms. There are a thousand voices who extol the value of screens. Most of them want to sell something or are speaking out of fear of being left behind. But we shouldn’t just accept all technology as it comes along just because we’re afraid.

Screens are bad for children. We don’t test them. I think screens should go under as much testing and scrutiny as medicines that we give children. I believe overuse of screens is a thalidomide of the 21st century.

Screens get between the mother and the child, the teacher and the child. If you see a child with an e-book, they go back and forth, swiping—they don’t know how to tell themselves the story.

Also, the New York Times recently came out with an article that said children who don’t write and draw are missing out on vital neuron development. Actual handwriting and drawing trains the brain in other ways; the brain learns from the hand.

Books should be books. E-books are fine for adults, but they should not exist in the picture book realm. Mine included.

How do you feel about all this mandatory testing in schools?

RW: Mandatory compulsive testing accomplishes nothing except useless paperwork and unfair ranking of teachers. Worse, the endless loops of scores never actually improve education.

What happens with education is that there is a layer of authority, the stratosphere above the teachers, particularly elementary school teachers, who I talk to quite a bit. That level of authority knows nothing about classrooms, children or teachers. It simply invents rules and enforces them. It’s a terrible way to run an education system.

I believe testing shows one thing: The home life of the child and whether the child is being read to.

What is the value of silliness in education?

RW: I wouldn’t call is silliness, I’d call it levity. Because silliness can very easily cross over the edge of good taste and intelligence. Everything in education should have intelligence behind it.

There’s a great case for levity. And relaxation and enjoyment. And simple storytelling and imagination. If that’s provided, children will learn. You don’t engage children by boring them.

Any plans to retire?

RW: I think retirement causes death! I will retire when I can no longer draw. Or when the airplanes no longer land at my airport.