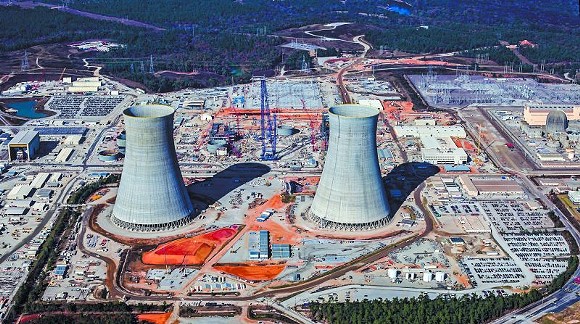

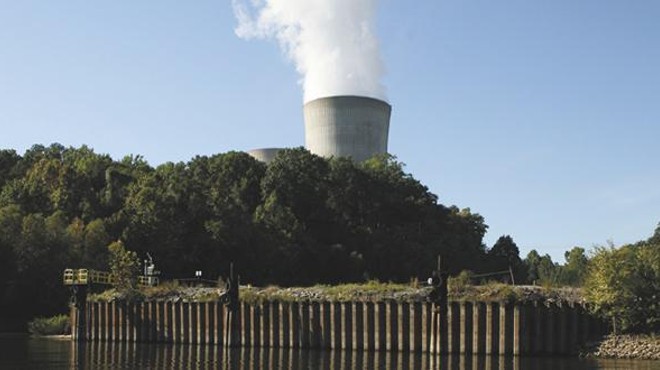

A PAIR of new nuclear reactors at Georgia Power’s Plant Vogtle, about an hour north/northwest of us on the Savannah River, were supposed to be up and running two weeks ago and sending electricity to the regional grid.

Instead, the project is still less than 40 percent complete.

Originally budgeted at about $14 billion, the expansion at Plant Vogtle is now by some estimations least $6 billion over budget and counting, with no real end in sight.

That much we already knew. But the big news last month was that the manufacturer of the reactor units themselves, Toshiba-owned Westinghouse, has put its North American operations into Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

That’s right — the company making nuclear reactors upstream of us is going bankrupt. Sweet dreams!

None of this stopped the chief executive of Georgia Power’s parent firm, Southern Company, from getting a 34 percent pay raise last week. Thomas A. Fanning is now up to $15.8 million a year.

In the meantime, since 2011 almost ten percent of your monthly power bill goes not just to pay for the Vogtle expansion, but to pay for the financing costs. That’s thanks to special legislation, the Nuclear Financing Act, passed by the state legislature and then-Gov. Sonny Perdue in 2009.

See the line on your bill that says, “Nuclear Construction Cost Recovery?” That’s what you’ve been paying to finance the Vogtle expansion in advance.

(It comes to 9.7 percent of your billed kilowatt usage, not your whole monthly charge. In South Carolina they’ve got it even worse — a planned expansion of the V.C. Summer plant north of Columbia is costing each SCE&G customer more than double what we pay each month, and they don’t even get an itemized bill.)

The Nuclear Financing Act essentially stripped rate increase oversight of this project from elected regulators at the Public Service Commission (PSC).

And customers are relieving Georgia Power of virtually all financial risk of its $6.1 billion share of the project cost, including interest on borrowed funds.

It’s quite a sweetheart deal for the subsidiary of Atlanta-based Southern Co., the nation’s second-largest utility.

It gets sweeter: As we reported back in 2010, the legislation has no cap for cost overruns, and doesn’t even have a way to refund customers if the project doesn’t even get completed at all.

What the hell is going on? Sadly, not much that wasn’t predicted over ten years ago when all this began.

“Most all the concerns previously brought to the Public Service Commission are now playing out in real time,” says Stephen Smith, executive director of Southern Alliance for Clean Energy (SACE). “The utilities have totally lost credibility and now we need regulators to do their jobs.”

In 2006, Southern Co. began seeking approval to double the number of reactors at Plant Vogtle. (The first duo, Units 1 and 2, was online by the late ‘80s.)

It was to be the first expansion of nuclear energy since the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster in 1979.

By 2009 the expansion plan had received approval from the PSC. If completed, the Vogtle expansion would make it the largest nuclear plant in the United States.

In 2012 — just a year after the nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan — the federal Nuclear Regulatory Council approved the planned use of two Westinghouse AP1000 reactors, a design the parent company says has greater safety parameters than the General Electric reactors at Fukushima.

As of this writing, not a single AP1000 has gone online yet; the first is set to go live at a Chinese plant later this year.

Project and reactor construction delays, and Westinghouse’s financial woes, are slowing new projects in China as well.

Since the Vogtle expansion was approved, the project has experienced one setback after another, all of them underwritten by Georgia Power customers, and almost all of them predicted by environmental watchdogs and media outlets such as this one.

In a grimly symbolic incident, in 2012 a reactor vessel set to contain one of the AP1000s literally fell off a train on the way to Burke County.

News of the accident, which involved no radioactive materials, didn’t reach the public until about a month later.

“Once again PSC staff time after time predicted delays well in advance of Southern Company admitting to them,” says Sara Barczak, High Risk Energy Choices Program Director for SACE.

“Once again there are revised commercial operation dates that represent another delay in the project.”

Originally, Unit 3 was supposed to be online April 2016. Then it was moved to July 2019. Completion for Unit 3 is now estimated to be Dec. 2019. Unit 4 was supposed to be online April 1, 2017. Then it was moved to July 2019. Completion for Unit 4 is now estimated to be to Sept. 2020.

The extreme delay, combined with a complicated pending litigation issue, prompted a new settlement agreement in the closing days of 2016, to reflect the new economic reality of the ballooning financing cost to ratepayers.

“There’s been a slight change in the financing situation because of the settlement reached at the end of the year,” explains Barczak.

“Interest is still going to be collected. But once the certified capital cost is reached, instead of being collected in advance it will go into a different type of accounting process,” she says.

“But customers will still be paying for financing costs far longer than expected, and ultimately will pay far more.”

Because of the huge delay, “Financing costs ended up representing the largest cost increases,” says Barczak.

“It’s like the longer you have a credit card not paid off, the higher the interest is. The interest ends up being what kills you.”

That’s why Barczak and other environmental watchdogs are frustrated with the settlement.

“Ratepayers are just going to pay for financing longer,” she says. “Because by 2017 both reactors were supposed to be operating by now, that advance payment will not be collected. There are no capital costs in the legislation.”

The 2016 settlement now targets a completed project date of Dec. 31 2020, but few observers have much trust in that target.

“This represents a 45-month delay. PSC public interest advocacy staff testified that even using a 45 month delay date, it was unlikely the new completion date can be achieved. It would require a threefold increase in productivity,” Barczak says.

“This forces customers to continue to pay for a facility where the utility cannot accurately predict the cost, and when or even if the facility will be completed, adds Stephen Smith of SACE.

“It’s like the longer you have a credit card not paid off, the higher the interest is. The interest ends up being what kills you.”

tweet this

Georgia Power originally said the financing plan would save customers over $300 million in the long run. But that was based on the original, now-obsolete timeline. Any savings realized are now more than outweighed by the cost overrun.

The Westinghouse bankruptcy adds yet another, and potentially very serious, layer of uncertainty to an already very uncertain project.

“Toshiba purchased Westinghouse in 2005-2006. They had developed a reactor design that most facilities across the country decided to go with,” Barczak explains.

“What panned out just recently is that Toshiba started losing big on these projects. They lost $6.3 billion on two projects combined,” she says.

“This bankruptcy has created a worst case scenario for electric power customers in Georgia and South Carolina. There are more questions than answers at this point,” says Smith.

“We see no path forward without some additional financial pain for customers.”

The bankruptcy is particularly tricky, says Tom Clements, executive director of SRS Watch.

“The loan guarantees for the Vogtle expansion run through Southern Co., not Westinghouse. Southern is not directly related to the bankruptcy,” says Clements.

“Once the bankruptcy court starts shifting costs around, you can’t predict what will happen,” he says.

Adding a twist is the fact that most of Westinghouse’s overseas operations aren’t included in the bankruptcy proceeding — raising suspicions that they are looking for a way to back out of the Vogtle deal.

“It’s pretty clear from their filings that they’re looking to us to take over this project,” said SCANA CEO Kevin Marsh, whose company is also contracting with Westinghouse for AP1000 reactors.

All of this is a far cry from the so-called “Nuclear Renaissance” at the turn of the 21st Century, when advances in technology were supposed to relieve the world of what at the time were high fossil fuel costs and an assumption of severe future scarcity.

With the Energy Policy Act of 2005 — a Bush-era initiative enthusiastically endorsed and enhanced during the Obama administration through generous loan guarantees — the future of U.S. energy looked to be a heavily nuclear one.

“After the Energy Policy Act of 2005 passed, over 30 new reactors were proposed, more than half in the Southeast,” Barczak says.

Then came the great recession of 2008, followed by a little thing called fracking.

Seemingly all of a sudden, the fossil fuel industry experienced a huge boom, both financially and in projected availability.

“We’ve seen the demise of the so-called nuclear renaissance,” says Barczak. “A lot of license applications for new nuclear plants were withdrawn.”

But not at Plant Vogtle.

At the time, the Congressional Budget Office was prophetic in its assessment of the state of the nuclear industry.

“If construction costs for new nuclear power plants proved to be as high as the average cost of nuclear plants built in the 1970s and 1980s or if natural gas prices fell back to the levels seen in the 1990s, then new nuclear capacity would not be competitive, regardless of the incentives provided by Energy Policy Act,” said a CBO report from 2008.

“Every single thing we said might happen did happen,” says Barczak. “Then Fukushima happened.”

The tsunami-induced failure of a reactor at the Fukushima Daichi plant, a disaster of such scope that its impacts aren’t fully measured six years later, wasn’t even a speed bump for the Vogtle expansion.

“We are committed to the project and completing the units on schedule and on budget,” said Southern Nuclear Co. spokesperson Beth Thomas at the time. “We’re certainly monitoring the events in Japan and our thoughts and prayers are with the people there.”

A lot of this momentum, Barczak says, it due to the unique situation of a utility building nuclear power plants with all the regulatory burden on the government, and most of the financial risk on ratepayers.

The Southeast, she says, “is in a weird situation in that we’re a regulated market but very weak on consumer protections. States like Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina all had legislators passing legislation to put extra burdens on consumers.”

The nuclear power industry, Barczak says, “isn’t exactly what you’d call a nimble industry. It can’t react to changes that sometimes happen very quickly. It’s based on the old model of, ‘OK you’re gonna have more people, so build a bigger power plant,’” she says.

“For the Southeast, if the coal paradigm seems to be going by the wayside, then we’re still in the nuclear paradigm.”

Noboby knows what happens next, though all eyes are on the bankruptcy court. With the precedent set for ratepayers to stay on the hook regardless of how much sunk cost is going into the Vogtle expansion, there is vanishing hope of a win/win solution for ratepayers.