RECENT EVENTS have caused quite a stir in my own neighborhood, the Thomas Square Historic District (where I sit on the neighborhood board), which contains most of what people think of as Starland, and the future home of "Starland Village"—the cause of the ruckus. (See my most recent column.)

One word sums up the debate: Gentrification.

So, as if trying to waste words in a high school essay, let’s go ahead and look at the M-W.com definition, shall we?

Gentrification: the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces poorer residents.

I actually like this definition (though I might replace “deteriorating.”) It is succinct but acknowledges that it is a very big issue, a “process,” which contains both good (renewal) and bad (displacement) and debatable (influx of...people you may not like).

Given its complexity, saying that you are pro- or anti-Gentrification is a bit like saying you are pro- or anti-Plate Tectonics.

Everyone likes mountains, right? They are beautiful and good for skiing (or snow-boarding if you prefer). Also, uplift and erosion creates the soil that we grow things in. Good.

But along with that we get earthquakes and volcanic eruptions that kill people and destroy cities. Bad.

Then there’s tectonic hotspots. They’ve created Hawaii and Yellowstone, but that last one might become a super-volcano that will render the Earth uninhabitable. Hmmm, debatable.

Must one take a pro- or anti- stance on Plate Tectonics as a whole? How about we try to understand it instead, and mitigate the bad stuff?

We do that already? Good. Seems to be the reasonable approach.

But the vast majority of people, when they bring up Gentrification, are actually speaking about just a piece of it, as if that piece is the whole. Thus, a discussion about Gentrification amongst a diverse group ends up being a conclave of blind men arguing about what an elephant is, depending on what part of it they currently grasp. (It’s an Indian parable—look it up).

So, let’s examine some of the different parties at the debate, the blind men as it were, and look at what part of the elephant they are grasping. (Note: these categories are not mutually exclusive.)

THE RENTER

Obviously, renters don’t want their rent go up. This is perfectly understandable: immediate self-interest. Nobody likes to pay more for something than they used to. Or to have to move to a less desirable neighborhood because rising rents have pushed them out.

To escape this cycle, if possible, you’ve got to grab some stability by buying something. Then you become...

THE HOMEOWNER

If you just own your own home, Gentrification can be a mixed bag. Sure, the neighborhood is improving and my home value is going up, but so are my property taxes, dammit. And it’s getting congested around here! And who are these new people? But maybe Trader Joe’s will finally look our way...

A homeowner’s view of Gentrification is likely to be directly influenced by how long they intend to hold on to their house (or pull out some equity), i.e. if and when they might directly benefit from the appreciating values that accompany Gentrification. And if they enjoy coffee.

If they own more than their home, they can also be...

THE LANDLORD

Ah, rents are going up. That’s a good thing, especially when demand is high and supply is constrained—then a landlord doesn’t even need to improve a property to make more money from it. This is “scarcity value,” and anyone who owns a scarce asset loves it for its scarcity, even if they won’t admit it.

So, be suspicious of people who own property and don’t want new things being built near them because of “Gentrification.” Could be that they just want to keep their scarcity value intact rather than having to compete with newer spaces.

DEVELOPERS and INVESTORS

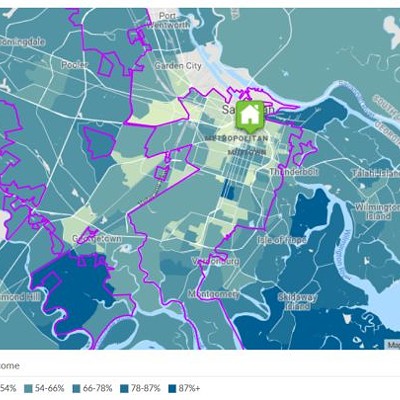

Gentrification, you say? Where is this? What area? Show me on a map.

To this group, Gentrification is a signal of unmet demand, and if they can get there to supply that demand before the next guy, they can make some money. The profit motive is pretty simple, but it can take many forms, depending on what they believe there is demand for (like those luxury apartments).

NEIGHBORHOOD BOOSTERS

Residents and business-owners within the neighborhood who are excited about the revitalization, but they probably aren’t saying “Yay, Gentrification!” as it typically has a negative connotation. They like new options. They like rising values. But they are probably crossing their fingers that the local favorites don’t get squeezed out.

PEOPLE WITH AN OPINION

We’re all in here. Our opinion is typically in reaction to the ideas of the previous two groups. Many subjective, personal gripes get thrown in here. What we don’t like magically becomes a facet of Gentrification. Parking issues. Hipsters. SCAD students. Buildings that are “too big” or “ugly.” Edison bulbs. That new place that isn’t the old place.

On the flip-side, the opinion might be about what the neighborhood “actually” needs. This is almost always something that there is no economic incentive for the private sector to do, otherwise they would have it—artist spaces, a playground, a community garden, a grocery store (with low prices!), low-income housing.

SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCATES

Many people are genuinely concerned for the well-being of others, and thus are concerned that rising values can displace current residents in an improving neighborhood, especially those with lower and/or fixed incomes. Focusing on this issue, to them Gentrification = Displacement.

NARCISSISTIC VIRTUE SIGNALERS

A toxic sub-group of the previous category. The Narcissistic Virtue Signaler wants to be seen being concerned about the well-being of others. A great way to do this is to speak loudly and judgmentally about Gentrification, shaming or shouting down anyone who “glorifies” the crime of Gentrification.

TRUE REDS

Some critics of Gentrification seem to actually have a much larger problem—that of the market economic system and the profit motive itself. I gather this from the content of their Facebook posts, and from the “100 Years of Communism” temporary frame that they put on their profile picture back in October. No, I’m not making this up.

So to those that seek to abolish private property and establish a command economy, maybe you should stop wasting your time protesting the new café and start researching emigration procedures. I hear North Korea has great parades.

NERDS

I’m one of these people. The nerd in me sees Gentrification as a fascinating subject, and wants to understand it as fully as possible. Thus, I also try to remain neutral about it, the alien economist observing from remove, which can drive others crazy. Pick a side!

I wrote my grad thesis (oddly called an “option paper” in my program at Georgia Tech) on how the property tax could be re-configured to achieve more efficient outcomes in the built environment, including a “taming” of gentrification.

I went so far down the rabbit hole with it that my advisor finally said, “Jason. Stop. Stop writing. Stop bringing me pages. You are done. Save the rest for a book.” I was trying to grasp the whole elephant.

Which raises the question: Can the whole elephant be grasped? Or is it better to focus on one aspect, due to its positive or negative effect, and ignore the rest?

I hope to explore this in future columns, delving further into the facets, interviewing people that fit into the categories I described above (if they will speak to me).

But for today’s conclusion, let’s all try to treat Gentrification more like the multi-faceted process that it is, rather than just the perfect ski slope or just the super-death-volcano. It’s not that simple.