Difficulty making ends meet? You’re not the only one.

Even though the recession has been over for ages and unemployment is down, more than 76 million Americans still struggle financially. Economist Rachel Schneider wanted to know how people are coping, so she and fellow researcher Jonathan Morduch tracked 235 low-to-moderate income households across the country for the U.S. Financial Diaries Study.

The study uncovered a “hidden inequality,” challenging notions about how people earn, spend, save and plan. It turns out that income stability is just as important as money itself when it comes to financial security, and the findings have become a popular book, The Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty.

A former investment banker, Schneider spent time as a VISTA volunteer and currently serves as the Senior Vice President at the Center for Financial Services Innovation. She will be the keynote speaker at Step Up Savannah’s Annual Meeting and Breakfast on Thursday, Oct. 12.

“By featuring Ms. Schneider, we begin community discussion on a subject that is underappreciated for its impact on a vast majority of working families,” says Step Up’s Executive Director Jen Singeisen. “We hope that this is the first step in addressing the causes of distress and inequality in our community.”

We spoke with Schneider about the gig economy, the difference between wealth and stability, and how reinventing the tax code can help.

Why are so families feeling so financially insecure, even if they’re making money on paper?

Rachel Schneider: A lot of is about volatility in their earnings. People are dependent on hourly wages, inconsistent schedules. We'll all aware that people don't have money saved; half of Americans can't easily come up with $400 in cash. Then you add the idea the people's income and spending are both highly volatile, and people are trying to manage their ups and downs around zero.

What we’re trying to say with the Diaries is that this is a distinct problem aside from whether people have enough money—the timing of when they have it matters.

What is the biggest misconception about people trying to make ends meet?

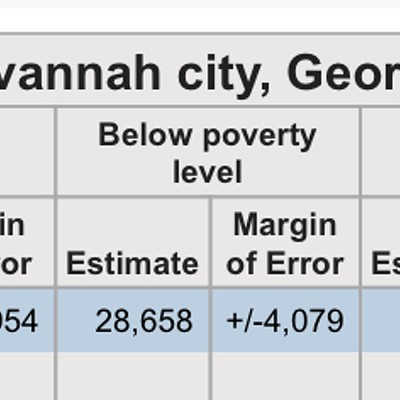

One of the more striking findings of our work is how people who have annual incomes that are middle class or considerably away from poverty level nonetheless have months of the year when they’re below the poverty level. So we have this false image of poverty as this permanent or at least this long term state. That’s true for about half the people who experience poverty; they’re poor for years at a time. But the other half are poor for two months, three months, and that’s a different problem to solve and still deserves attention.

What is the difference between wealth and stability?

We’re not concerned with it as a social policy matter, but I would not assume that people who have wealth aren’t necessarily stable. And income doesn’t perfectly correlate with financial health.

What I would say is that wealth is one of the ways to achieve stability, but not the only one. But coming up with wealth bring risks of instability on its own. In order to achieve wealth, you have to take a risk of some kind. You have to invest in education, in housing, in a business—that’s how you create wealth. So instability is very much a challenge for people as they pursue wealth. Plenty of people decide they would prefer stability.

Was that surprising to you?

Not at all. I’ve been doing this work for a while now, and I’ve sat in on focus groups where some well-meaning leader would say to a group of low-income people, “What are your aspirations for the next five years?” and they would look at her like she was an idiot! They’re thinking about paying next month’s rent, and when they can do that regularly without worry, then we’ll talk about five years from now.

One of the things been compelling to me about this work that’s important to understand is that it’s not people’s fault. They’re working really hard and doing a good job at forestalling disaster. Sitting down with someone seeing how resilient and resourceful they are really opened our eyes to see that the system is stacked against them.

What needs to happen for more Americans to have more financial stability?

Well, the fact that so many people work full-time and still can’t afford to live is really shocking to some. Take the gig economy—people are glad to have Uber come to their town, but remember that Uber provides no step up. There’s no opportunity to rise to the manager level. You’re just driving. In a tourism-based economy, people are dependent on tips, which is also very volatile.

So when communities are thinking about the jobs they’re attracting, they can do more to require more of employers to invest in the people they hire. That means benefits and a living wage, but it’s also about scheduling. A lot of the volatility we saw people experiencing is the result of working jobs where they have inconsistency in how many hours they work from one week to the next because their employer sends them home when business is slow or they vary the schedule. That’s really hard for people to manage; it’s hard if you want to have a second job or you have kids or you want to go to school part-time.

Are there policy level changes that America can make, even though it probably won’t right now?

[laughs] Well, we can still talk about it. From a conceptual perspective, once you see that people are struggling with consistency, there's a whole set of policies that follow. Our tax subsidies for saving, for example, are all about the long-term, retirement and home ownership and 519 plans for college. But we don't provide any equivalent incentives if people want to save for near-term stuff, which is often more urgent.

You see incredible leakage from 401K accounts where people are saving for retirement, then something comes up that is more pressing that retiring 40 years from now. So they withdraw in spite of the penalties to pay for the roof that’s leaking or the car that’s breaking down.

I’d like to see more of the tax investment be more towards near term savings in the first place. How can we help middle class Americans put away the money they’ll need for three months or six month or a year from now? If we’re allegedly going to break the tax code and put it back together, why not do it with this in mind?

Do you think we are ever going back to a place where government steps in to help the middle class?

I think it’s really worth pointing out that manufacturing jobs, which we lionize now as the epitome of middle class security, were terrible jobs at the dawn of the industrial revolution—terrible! You can’t get though a history class without learning about the fires that killed garment workers and kids dying in factories. Those jobs became good jobs through a combination of workers standing up for their rights and unionizing, government imposing laws, and employers who saw that they could get better productivity out of workers who weren’t dead tired.

Ford Motor Company is always credited with the first 40 hour work week, and decades later the government made it a requirement. We need some version of that now. We’re going through as big of an economic shift as we were back then, and we’re shifting from a manufacturing economy to a service economy—some people call it a “knowledge economy.” Whatever it is, the jobs that exist today are different than the jobs that existed 50 years and now we need a new set of expectations of what work entails. We need new investments in ourselves as a people.