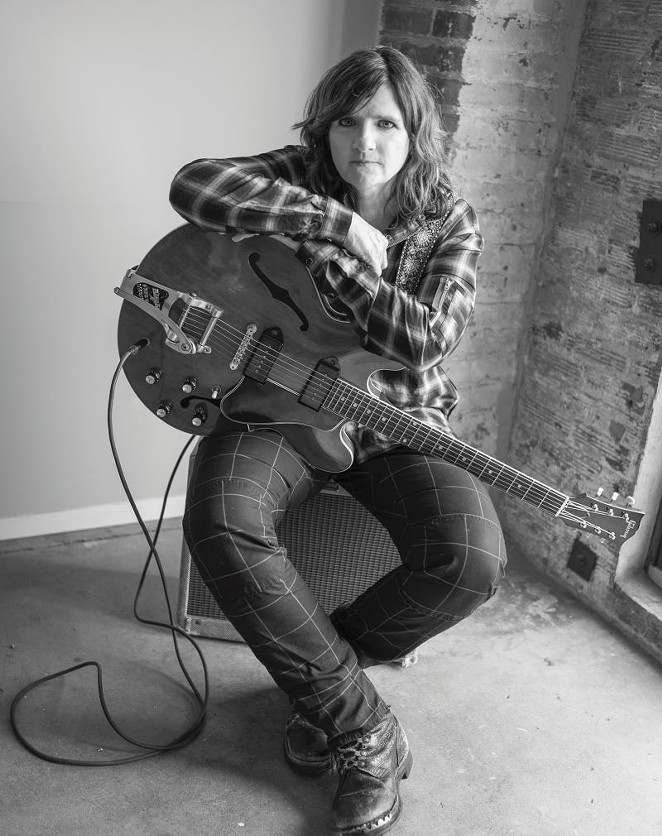

AS ONE HALF of Indigo Girls, Amy Ray has woven herself into the fabric of American music history. The duo came along at a time when what they were doing wasn’t really being done by anyone else, and they helped pave the way for the resurgence of female-led folk rock in the 90s that ushered in the era of Lilith Fair. To this day, Ray and fellow Indigo Girl Emily Saliers continue to release new music and tour relentlessly.

Both Ray and Saliers have released solo albums, with Ray producing six since 2001’s groundbreaking Stag. While her early work was straight-up punk rock, her last two albums have explored Ray’s love of country music.

Her new release, Holler, is the second country album she’s done, but it also leans into the energy of her punk records while incorporating elements of R&B and soul.

Ray, who’s coming to the Emma Kelly Theater at the Averitt Center For The Arts in Statesboro on Nov. 9 for an acoustic performance with legendary country songwriter and Savannahian Tony Arata, enlisted an all-star cast for her magnificent new collection of songs.

We talked with her ahead of the show to find out the making of Holler and the themes she tackled when writing the lyrics.

CS: This record is a lot larger in scope than your last country album - a lot of these songs even have a sort of punk edge to them. Was that intentional? What made you go in this direction, even with putting horns on songs and that kind of thing?

Amy: The horns were inspired by a record from a guy named Jim Ford called Harlan County that someone turned me on to. I listened to it, and the way he did the horns was so good. It's that late 60s horns in country thing [laughs]. I was listening to Blake Mills a lot, too.

His last record is insane.

It's so good. He's so good at breaking the barriers and having things be wide open. So that kind of inspired me to make sure I didn't limit myself. But I wanted to make a country record that was southern, though I didn't stay away from stuff about being a Southerner and the things that we wrestle with. Our history, the present, and how we wrap our minds around all that. That was something that I was addressing mentally, and it came out in my songs.

It was different from [2014’s] Goodnight Tender, and was a little bit more active in that way.

You’ve always done this to an extent, but this record does address this idea of being a Southerner in today’s climate. Was that a calculated theme on the record or was it an organic thing?

I think it was more like, I’m writing all these songs and it’s during a particular period of time so what’s happening is what I’m thinking about. It becomes a theme, even when you don’t intend it to be just because it’s where your head’s at.

In some instances, I might have been working on songs that might not fit in with what was happening on the record. So at some point, I saw a direction that was happening. It kind of steered me in the way I was writing and became what I would focus on as far as finishing songs.

Is that something that always happens when you write, or was it really only with this record where you experienced that snowball effect?

It actually happened on Goodnight Tender too, where I had songs that were hanging together in a certain way and I wanted to make a record that was less attached to present issues and a little more timeless. So there might be a song that has a Woody Guthrie vibe in the way of talking about humanity, but it wouldn't directly - like "Jesus Was A Walking Man" - talking about specific countries and wars and refugees.

I think on Goodnight Tender I had a very clear intention that I didn’t want that to enter into the process. I wanted to make this thing that was kind of free of all that. It was an exercise to see if I could do it, really.

With this record, I wouldn’t have been able to do that because I feel like I’d already done it. I wanted to move to another place, and I had this feeling that I kind of missed the punk rock stuff I’d been doing. That kind of leaked out in very nuanced ways.

Another thing about this record is that there are little interludes and shorter pieces that thread the album together. Was that inspired by any particular album? You’d never really done that before.

I hadn’t! Brian Speiser, who produced this, wanted to do something like that. The song “Sparrow’s Boogie,” I started writing that as a ballad. So I thought we could use the earlier form of what it used to be before it became the boogie song that it is, and we could team that up with a piece of this lullaby that I’d finished but decided to use as a bonus track.

The prelude, Brian wanted to have it feel like you were still in Goodnight Tender land - that kind of mellow, cowpunk, riding across the plains kind of vibe. Brian as a producer really stepped in on this record and he kind of directed it that way.

There are so many interesting things about this record - “Sparrow’s Boogie” has some really interesting timing things, and there are slight tempo shifts throughout. Were you using a click track, or were you tracking it all live so you could push tempo and things like that?

It was all live. The only thing that wasn’t live was the strings and horns. They played live as a section to tape, but the songs had already been recorded. And then all the guest vocals were done kind of remotely. But some songs we used a click track on and some we didn’t. We ditched it sometimes because it messed up the feel of the song, you know?

Jim Brock, the drummer, it was always his decision. We knew that we would shift around a bit in certain songs. It had to be a comfortable shift where it wouldn’t be distracting, but sometimes the click track would be hard to move around with.

For us as a band, the way we play, sometimes click just wasn’t working and sometimes it kept us completely in line.

How’d you get Vince Gill on the record? Vince Gill of The Eagles, I should add.

I know, right?

It's weird that in 2018 you can say Vince Gill of The Eagles and Neil Finn of Fleetwood Mac, but that's the world we live in now. How did Vince end up on the record?

I got so lucky. He is someone that I heard in my head. I love his voice, and I said "I hear his voice on this song. I hear Brandi Carlile on this song, and I hear Vince Gill on this song." And I knew I could ask Brandi, but I don't know Vince.

I was talking about it casually around Allison Brown, the banjo player on the record who lives in Nashville and knows everybody. She goes, “I know Vince! He’s a friend. Do you want me to ask him for you?” And I was like, “Yes!”

Yes please!

He’s quite the gentleman. He’s like the prince of Nashville. I can’t say enough good about him. It was just a lucky thing, you know?