THE LEGEND of W.W. Law is already a permanent part of Savannah’s story.

One of the most influential community leaders of the last century, the former postal worker impacted countless lives, and his contributions continue to reverberate and long after his death in 2002.

The president of the local chapter of the NAACP from 1950 to 1976, he championed African American equality and led dozens of non-violent protests against segregation in the 1960s. He was a Boy Scout leader and everyday historian, informing multiple generations about events and perspectives that the mainstream narrative left behind.

A passionate collector of African American art, photography and artifacts, he amassed thousands of items that have been archived by the City of Savannah and are occasionally curated for display physically and online.

But few understand the part Law played in preserving the city’s character so celebrated by visitors and locals today.

The driving force behind the restoration of the Victorian-era King-Tisdell Cottage and nearby Beach Institute, he remains one of the primary players in the efforts to protect Savannah’s formidable architectural legacy.

“A lot of people think of him as a Civil Rights leader, but he did a lot to bring awareness to historic preservation, especially in African American neighborhoods,” says Luciana Spracher, Director of the City of Savannah’s Research Library and Municipal Archives.

“He did a tremendous amount to make sure that African American history was included at the table.”

As part of the commemorations for Savannah’s 50th anniversary as a National Historic Landmark District, city leaders have designated September 19-23 as W.W. Law Preservation Week and are hosting a variety of activities highlighting places that might no longer exist if it weren’t for his efforts.

On Monday, Sept. 19, the city has partnered with the Historic Savannah Foundation for a panel discussion that sets the lay of the land. “W.W. Law’s Influence on Today’s Preservation Landscape in Savannah” brings together a trio of knowledgeable locals: Real estate guru and Downtown Neighborhood Association founder Dicky Mopper, affordable housing developer and former HSF chair W. John Mitchell, and Melissa Jest, the African American Program Coordinator for the Georgia Historic Preservation Division. The schooling starts at 6pm at the old Kennedy Pharmacy at 323 E. Broughton Street, followed by a reception.

The following day, Tuesday, Sept. 20, Savannah native and professional tour guide Johnnie Brown fires up his air-conditioned van for an expedition to several Law-related sites, including Laurel Grove South Cemetery and the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, housed in what was formerly the city’s largest black-owned bank.

Brown grew up learning about Savannah’s African American history at Law’s knee in the 1970s, watching the city’s crumbling buildings transform into valuable properties through the efforts of HSF and a brand new institution called the Savannah College of Art and Design.

“I lived behind the King-Tisdell Cottage as a kid. I started volunteering at the museum, and he kept teaching me things,” says Brown of his mentor’s persistent lessons.

“People didn’t appreciate downtown back then, everybody wanted to move out to the southside. But he truly believed part of being a leader was to preserve what’s here for future generations.”

Brown took over Law’s Negro Heritage Tour company in 2001, renaming it the Freedom Trail Tour. The van leaves at 10am from the Savannah Visitors Center on MLK Blvd.

If walking is more your speed, join author and preservationist Beth Reiter on Wednesday, Sept. 21 at 10am for an expedition through the historic Beach Institute neighborhood on foot. Reiter, the former director of Historic Preservation at the MPC and current owner of Savannah Architours, has intimately researched this area, from its many dwellings built by free people of color on the eve of the Civil War to Law’s campaign of stewardship.

“Many of these families immigrated to Savannah from impoverished and war ridden countries in the Caribbean and were able to start a new life here in difficult times,” says Reiter, adding that many who lived in the neighborhood were women who ran schools to educate slave children at a time when that was punishable by law.

All of the above events are free and open to the public, though space is limited and reservations are required to [email protected] or (912) 651-6411.

You might be a bit worn out by now; you wouldn’t be the first who had a hard time keeping up with Mr. Law. On Thursday, you can continue to explore his legacy without leaving the house with the launch of the city’s new online exhibit, “Law and Preservation.” Curated from Law’s own collections, the slideshow includes photographs, correspondence and awards that document local, state, and national recognition. View it starting Sept. 22 at savannahga.gov/wwlaw.

Friday, Sept. 23 brings a highly relevant intersection of two of Law’s passions, preservation and Civil Rights, when the Georgia Historical Society adds a new stop on its Georgia Civil Rights Trail. A historical marker will be erected near the site where in 1960 three young NAACP members were arrested for sitting at the lunch counter at Levy’s Department store, which is now SCAD’s Jen Library.

That incident spurred the Savannah Protest Movement and its toppling of the entrenched local government, led by Law and fellow activists Hosea Williams and Eugene Gadsden. A program featuring those who were there begins at 10am at Trustees Theatre at 216 E. Broughton Street.

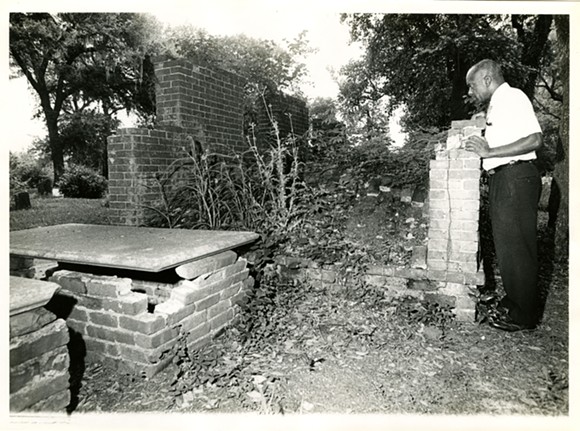

W.W. Law Preservation Week closes with an invitation from the city to visit the sites mentioned above, though the work continues to present a challenge. Laurel Grove South Cemetery has been an official burying ground for African Americans since 1853, separated from its white, northern counterpart. In the 1970s, Law “almost singlehandedly” re-identified hundreds of historically significant grave sites and demanded the city allocate resources to improve the grounds. But many of its oldest graves are unmarked and records were poorly kept, leaving its handmade tombstones and undocumented history vulnerable to the unsympathetic march of time.

After Law’s burial at Laurel Grove South in 2002, the city dispatched a dedicated crew to rebuild crypts and reset headstones, though documentation remains a formidable task without Law’s vast memory of local African American lore.

“We would like to get a full survey of Laurel Grove South. It is a bit of mystery what all is there,” says Sam Beetler, the conservation coordinator for the City of Savannah Department of Cemeteries.

“What we’re working on now is the slave burial section, trying to find all the information we can so we can properly interpret the site. But a lot of the headstones are broken. We’re doing a lot of conservation treatment to make sure they last as long as they possibly can.”

Such careful preservation of the past is essential if future generations are to know it, and Law spent the last part of his life working to ensure that the city’s narrative continues to include as many important African American sites and architecture as possible.

He seemed to understand that though no matter how much Savannah would grow and change, its most valuable asset would always be its history.

As his protégé Brown puts it, “He was telling us this was going to happen 40 years ago. He was a visionary.”