When the news broke July 2 that Meddin Studios had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, Nick Gant knew what people would think.

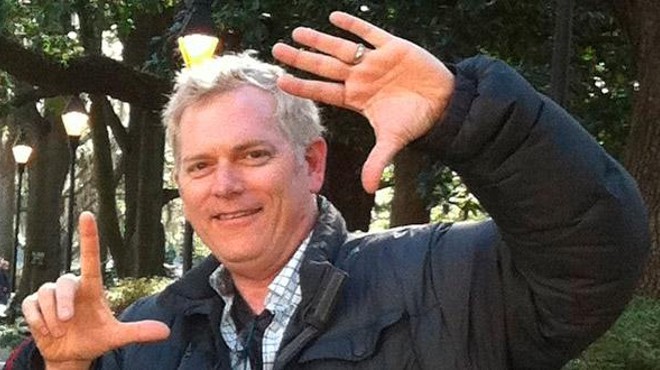

"We haven't failed because we didn't do what we were supposed to do," explains the 36-year-old founder and creative director of Savannah's state-of-the-art digital production facility. "We're failing because somebody doesn't want to pay their bill. We won't make that mistake again."

Gant is involved in a contract dispute with Radioactive Giant, the California filmmakers who shot Killing Winston Jones in Savannah last fall.

He maintains the movie's producers owe Meddin money; the producers, in turn, say that's a bunch of baloney. They've filed a countersuit, claiming Meddin owes them money.

We're talking many thousands of dollars.

This sort of thing is common in Hollywood, where handshake deals are conveniently forgotten, and contracts sometimes aren't worth the paper they're printed on. Movie-related lawsuits are a cottage industry.

In Savannah, a smaller market with comparatively fewer opportunities, it could be a devastating blow.

"If we fail," Gant says, "it's gonna be a long, long time before another studio or production company comes in here and says 'I'm going to invest in this community. If they didn't make it, why would I make it?'"

According to Gant, of the 11 independent films that have used his facilities and/or equipment, only two — Winston Jones and the Italian production Enchanted Amore, also shot in late 2012 — haven't signed the final check.

The problem is, there hasn't been a feature project at Meddin in their wake. Not one.

Which, frankly, has Nick Gant a little worried.

"I think it comes from bad perception," he says. "If you call the producer that came before you, and that producer says 'I'm upset. I have a lawsuit with them,' that person is going to stay away from Savannah."

With 22,000 square feet of soundstages, tech studios and office space, Gant's operation — housed in the old Meddin Brothers meat packing plant on Louisville Road — is tiny compared to production facilities in Los Angeles, New York, or even Atlanta.

But Gant, who with business partner Jon Foster began Meddin in 2010 with a combination of investor capital and a loan from the Small Business Association, saw a niche opening up in little ol' Savannah.

"For low-budget movies to come here, they want to have services they can afford, and they want to try to create relationships," he explains. "You have to start somewhere to build a community."

Filing Chapter 11 was a precautionary measure, to protect his investors until the legal matter is resolved. "I chose to file to buy time to move Killing Winston Jones out of superior court and into federal court," Gant says. "They have tougher and more strenuous guidelines, none of that 'he said, she said' stuff."

There are numerous bad-faith issues in the suit and countersuit between Meddin and Radioactive Giant. So far, neither side has budged.

Meddin's conflict with the producers of Enchanted Amore (now re-titled Four Senses) is fairly straightforward: "The only thing that they did was go four days over budget," says Gant. "Up to that point, they were paid in full."

These two relationships have gone south, but Meddin — which produces TV commercials, corporate films, audio and still photography projects and more, along with its movie work — has several that are so rugged they've strengthened over time.

Gant and company helped SCAD professor Annette Haywood-Carter make her film Savannah in 2011, and during the early production phase Haywood-Carter brought California-based producers Randall Miller and Jody Savin to Meddin.

"I had such a good experience with Savannah that I came back to Meddin a second time," says Miller, who directed the soon-to-be-legendary CBGB at the studio last summer. "And I think that speaks more than anything. I really like Nick, and I like what he's set up. It's really great."

Opening nationally Oct. 8, CBGB tells the true story of Hilly Krystal (played by Alan Rickman), who turned a seedy New York nightclub into the American epicenter of punk music.

"There's such a wealth of talent in Savannah, because of the school," Miller adds. "There's all these young, excited folks. If you need extra PA's, or people in the art department, or extras. That's what really makes it work. That adds a whole other level.

"For me, making movies is about the vibe. It's about where you go and the people ... Nick's a great guy, and so accommodating, and the folks in Savannah are really nice people. I've gone to lots of places, and they have all the equipment and everything, but the people aren't nice."

Georgia's incentive for filmmakers is nice, and attractive: Under the Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act, companies get up to a 30 percent tax credit for money spent on production in the state. There are union crew members in Savannah — although there are many, many more in Atlanta, where the Georgia Film Office is located, and in Wilmington, the film capital of North Carolina.

"We're the red-headed stepchild in this thing," Gant believes. "You don't pick up the phone, and the Atlanta union says 'Go to Savannah.' Or Wilmington. Either way, it's a four-hour drive. Because we're kind of out here in the middle of nowhere.

"The tax incentive goes into the community. If you're filming in Savannah, but paying all these people that live in South Carolina or North Carolina, that incentive's not being used the way it's written. People are walking out of our state with it."

With the ultimate aim of kick-starting a bigger film community in Savannah, in 2012 Gant and his investors made an offer on the old CitiTrends warehouse on Fahm Street. At 2.64 acres, the site would allow for a gigantic expansion of Meddin's facilities.

Expansion, he says, "would mean a national presence. And with that national presence, we would've had a bit more leverage, to create stronger relationships. People would look at us and say 'They now have something we can come to.'"

The largest single soundstage was envisioned at 22,000 square feet — the same size as the entire existing Meddin building.

After the competition (Chatham County) backed away, Meddin's offer ($3.5 million) was accepted in November. Two months later, Meddin paid CitiTrends $25,000 in earnest money, along with a letter of commitment.

Around Memorial Day, after a series of mandatory property reviews had been completed, and engineering issues sorted out, Gant and his partners were preparing to close on the new facility. They put the Louisville Road site up for sale.

Out of the blue, they were notified that the Fahm Street building had been sold to someone else.

Still optimistic that Meddin will not only survive, but eventually move into a larger space, Gant is trying to look past the lawsuits, the bankruptcy filing, the bad publicity and the CitiTrends disappointment. Miller, his wife and co-producer Jody Savin and their Unclaimed Freight Productions plan to return to the studio in the fall to shoot their adaptation of Gregg Allman's autobiography My Cross to Bear (several alternate titles are being considered, according to Miller), and the Spongebob Squarepants 2 crew will be dropping in, too.

Haywood-Carter's Savannah premieres Aug. 23, followed closely by CBGB. This fall will also see the release of two more low-budget indies filmed at Meddin: The comedy Crackerjack (from executive producer Jeff Foxworthy) and the horror yarn Breaking At the Edge.

Nick Gant is down, but he's not out. He retains his unshakeable belief that Savannah and the movie industry should — and will — be on the best of terms.

"You take a film-friendly community like Savannah, where you can come here and get permits for free, you can shoot in a lot of spaces," he says. "People are not overwhelmed or exhausted from film production. Now add to that the tax credit.

"Add to that a facility like ours, where we provide a 'pitch to post' space, where you're not nickel and diming somebody. You're not trying to get them to bring something from that state to this state, to that state.

"They literally come in this house, they sit down with a laptop, and they leave with a movie."