WE HAVE a disconnect about waste. Shell middens are interesting. But landfills are gross.

They’re the same thing, only separated by thousands of years.

“Just because it’s my time’s rubbish... doesn’t make it less significant,” says Savannah painter Isaac McCaslin. “It makes it more significant.”

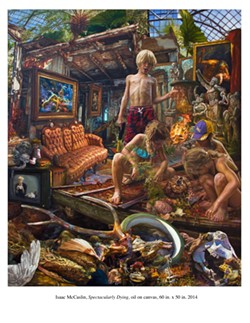

McCaslin thinks about trash. He creates what only can be described as large, oil-based “mental landfills.”

A dump not far from his home provides inspiration. He walks in the refuse and collects modern artifacts of our throw away culture.

“None of my paintings are depicted in a real space,” he says. “I just look at them as my mind.”

In the few short years that he’s lived here, McCaslin’s monumental pieces of flying brain detritus have earned him a reputation as one of the city’s most gifted painters.

Each painting has scores of elements. Snakes, sofas, computers, balloons and Roman ruins peek out in fantastical landscapes drenched in dark hues and odd perspectives.

You could spend hours describing them.

“I can’t just stick to one idea when I have new ideas and I’m making something,” he says. “So it just builds up.”

Each painting is like an archaeological dig. You sift through layers of cast-off memories like a psychological analysis. Lie down, Mr. McCaslin. What do you see?

The snake in “Spectacularly Dying” comes from a camping trip. The artist saw his nieces and nephews, depicted in the painting, playing with a lizard.

The pushcart in “Collector of Fine Things” comes from a California hitchhiking trip. He spent a lot of time with homeless people.

The busts in the same painting come from a visit to the High Museum in Atlanta. And it goes on and on like this, piled high, Bacon Park and Chevis Road style. “The more there is for me, the more of a puzzle it becomes,” he says. “I like the puzzle aspect of it.”

McCaslin can add elements to his paintings for months. The end is never clear. And the work of getting to the end comes in fits and starts.

Like other creative people, he describes his most productive times as fleeting, like a freak rain shower or a winning lottery ticket.

“The zone doesn’t happen a lot. It’s a special place,” he says. “If you get in the zone, stay awake for as long as possible. I can go nights without sleeping if I’m in the zone.”

He’s known for working days on end in his Starland District studio. I bet that’s the same way Rubens and Veronese worked.

Peter Paul Rubens is a 16th Century Flemish name I got from McCaslin’s lips. And Paolo Veronese is a 16th Century Italian name I got from art history.

Either way, we’re talking about the Old Masters. Part of what makes McCaslin’s paintings so special is this connection between the very old and very new.

“From a materials and techniques perspective, the way I see it is that it’s really hard to beat the Renaissance masters,” he says.

Even I see the connection. And I’m no art history expert. Veronese happened to be a mannerist painter, someone who bended reality to include many elements.

“They stopped caring about realism as much and started giving way to distorting space,” McCaslin says.

Only El Greco and the rest painted angels, counts and saints. McCaslin’s “landfills of the mind” contain much more mundane objects of contemporary living.

Is it beautiful? Definitely.

“Don’t let anybody tell you what’s beautiful,” he says. “Be persuasive about what you think is beautiful and interesting. And use that power of persuasion to make your statement loud and clear.”