I WAS a few minutes late for the bi-monthly board meeting of the Flannery O’Connor Childhood Home, but I still took a moment to compose myself on the stairs.

There’s something about entering this modest, Greek Revival townhouse-cum-museum that requires correctitude, as if the author and her family still lived here, and you don’t just rush in with your sunglasses falling out of your purse and lipstick on your teeth.

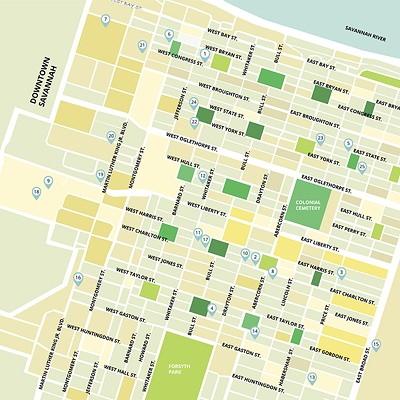

Offering an apologetic whisper, I squeezed in at a corner of the dining table, where my fellow board members were munching on cookies and discussing the details of the upcoming Flannery O’Connor Parade and Street Fair, set to take place this Sunday, April 10.

The Sweet Thunder Strolling Band had been booked, the local authors procured for the Book Lady’s vending tables.

One small matter remained.

“So, who wants to be the gorilla?”

A few of my fellow board members politely stared at the antique china cabinet that houses first editions of the author’s books. Others engrossed themselves in the budget spreadsheets expertly prepared by treasurer Christian Kruse. President Bishop Kevin Boland cleared his throat. Secretary Allison Hersh held her pen poised above her legal pad, ready to record the minutes.

Since I joined this board of brilliant and competent people last fall, I have found myself qualified to contribute very little, other than helping Mary Lawrence Kennickell arrange the snack table at September’s Ursey Memorial Lecture with Roxane Gay and volunteering to drive the best-selling author to the airport.

Even then, distracted by my own fangirl chatter and the seemingly sudden sprouting of the Tanger outlets, I managed to miss the damn exit. Poor Roxane Gay probably thought I was trying to kidnap her and dump the body in some remote South Carolina outpost in the vein of the Misfit in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.”

Now here was an opportunity to redeem myself from that terrible, awkward failure of duty. I slowly raised my hand. Joseph Schwartzburt raised his eyebrows. Ann Moffett smiled at me encouragingly.

“I’ll do it,” I said, lifting my arm higher and waving like a prom queen. “I will be the gorilla.”

The more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea. The lively parade that takes place every year in Lafayette Square outside “the childhood home” (as it’s referred to in order to differentiate it from the author’s adult home, Andalusia Farm in Milledgeville) is one of the reasons I joined up in the first place, with its unique combination of literary homage and reverential silliness.

Plus, I’ve totally got the skills for once. Not to brag, but I served as the mascot of the high school football team my sophomore year, spending every Friday night trying to keep up with the pom-pom squad on the sidelines and out of the way of the marching band.

Since my school had won the Arizona state championship two years before, it was afforded two mascots, a boy and a girl horse. My friend Cathy and I rotated between the full body suit of the boy horse and the far more preferable girl costume, a heavily-eyelashed equine head and an old cheerleading uniform.

No matter what, we looked like teenage disasters at the after-game dances in the gym, where we mostly spent drinking stolen wine coolers in the locker room.

Anyway, I figured I have the fortitude to pull off a few hours as an ape with no choreography. But I felt I needed more background to fulfill the role justly, sniffing out meaning and context through the nostril slits of the fur mask. (Call it gorilla journalism, if you will. Hell, you probably already did.)

Though I remembered it making appearances in her work, I wanted to know what a gorilla is doing at a Flannery O’Connor parade. But first I had to understand why a literary icon universally described as “reserved” and “private” has such a wacky parade in the first place.

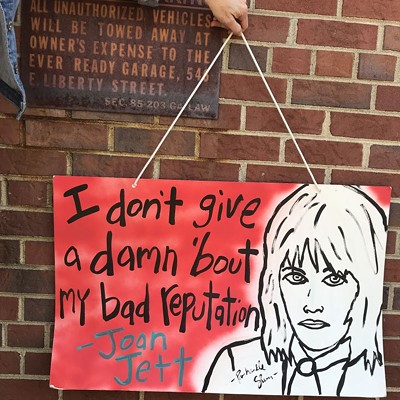

The answers lay with artist and former FOCCH board member Christine Sajecki, who discovered an edict from the 1970s proclaiming March 25, Flannery O’Connor’s birthday, a city holiday. She already knew that percussive ringleader Andrew Hartzell—now on the current board—used to throw spontaneous (i.e. unpermitted and unsanctioned) parades back in Portland, and together they invited their favorite literary-minded rebels to reclaim the celebration.

The first seditious procession took place in the late afternoon of MLK Day 2012 around Lafayette Square, a ragtag bunch of 20 carrying signs bearing Dr. King quotes and the Flannery battle cry, “Beauty is our money crop.”

The following year, the parade was officially adopted by the FOCCH and acquired legitimate paperwork, but it still retains the atmosphere of family-friendly anarchy, with its azalea crowns and chicken poop bingo. Over the years the event has become a beacon for anyone with an askew view of the world, taking a cue from the writer’s famous quote about recognizing freaks. All the weirdos must converge, or something like that.

Still, it’s hard to picture the honoree joining the fray. Instead, I imagine her observing wryly from her former bedroom window, thinking up ways to describe yet another ludicrous band of Southern idiots.

“I don’t know that she herself would enjoy it,” agrees Christine, who moved to Baltimore a couple of years ago and was back in Savannah last week for a short spell with her husband and adorable six-month old son, August. (Perhaps you bid on her beautiful encaustic painting at the Southern Discomfort art show at Non Fiction Gallery last Friday?)

“Her writing was radical, but she was a fairly proper person. I doubt she would appreciate having such a spectacle made of herself.”

But perhaps the devoutly religious O’Connor would recognize the earnestness in the absurdity. Surely of all people she could see that the flagrant freakiness is meant in its way to be an alignment of faith—not a fragile kind of belief that dissolves into the ether outside of the church sanctuary, but a clear conviction that holds up under the hard, grotesqueness of human nature.

Anyone who has attended the parade knows that when Father Michael Chaney preaches “Where’s all my sweetness gone?” as the afternoon melts into the long shadows of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, the plea is not satirical but sacramental, a heartfelt testament to the mystery that binds us here together under heaven.

But back to the gorilla. A guy in an ape suit shows up in the short story “Enoch and the Gorilla” and again in the novel Wise Blood as Gonga the movie star, though his scenes are brief. Christine says the primate costume was embraced as a symbol that could be easily represented in the parade, along with the prosthetic leg in “Good Country People.”

However, as you may recall, Flannery’s gorilla is kind of a jerk.

He tells Enoch to “go to hell” when they shake hands, and his mean response provokes Enoch to stalk him around town, beat him up and steal his simian identity.

On one hairy hand, I can empathize with the gorilla’s bitterness, as I know a little something about wearing a full-body fur costume in the heat before the advent of fancy sweat-wicking under armor.

Plus, Enoch is pretty annoying and definitely creepy, especially when he is fleshed out more deeply in Wise Blood.

Yet it would be wholly inappropriate to embody a literal performance of the literature and have some parent smack me upside the head with a mannequin leg. So I continued to dig for my motivation.

I sought deeper analysis of the character from Michael Schroeder, an English professor at Savannah State University who happens to be the Vice President of the FOCCH. (“I guess that means I’m in charge of vice,” he laughs.)

With a good teacher’s deft way of teasing out coherent thoughts from dull minds, he led me through a short discussion on what the animal imagery might represent.

“Many of O’Connor’s human characters act completely out of impulse,” Professor Schroeder reminded me. “And we know that she was very faithful. Do you think there’s a connection?”

We bantered about basic instincts and the longing for spiritual redemption, about how crassness and even violence doesn’t preclude even the worst sinner from turning towards heaven, as we witness in the denouement of Wise Blood.

I scratched my head and snacked on a banana, working out how free will is still the only thing that separates us from the apes.

The evolution of the soul is a topic we can explore more directly in the posthumously published A Prayer Journal. Devoid of the signature sardonic vinegar in her fiction, this slim volume of letters to God reveals the purity of Mary Flannery O’Connor’s lifelong dance with devotion and doubt of her own spiritual worth.

“I don’t want to fear to be out, I want to love to be in,” she writes of hell and heaven. Though she is referring to the supernatural realms, this might also speak to our need to belong, to feel at home in a world that so often seems dangerous and unfair and just plain mean.

So while the patron saint of Southern freakery might offer appalled arched eyebrow were she to glance down upon Sunday’s colorful kooky pageant, I hope she would also see the comradery, the goodness, and the inclusion carried out in her name.

It might be as hot and humid as a sinner’s armpit on Sunday, but I will rejoice as I don the fur suit, not as a penance but an honor.

And though I forsake Gonga as inspiration, I cannot promise that I won’t break out the cheerleading moves.