AS A RULE, if someone shows up late to an interview, I'm gone.

I’m a busy lady, and if we’ve agreed on a time to talk, I don’t take kindly to being left hanging.

I sent my interviewee a text at ten past the hour and haven’t heard back. My friendly server at Carey Hilliard’s asks once again if I’m going to order.

I’m table-tapping out the Christmas music blaring from the speakers when a return text pops up:

Sorry got stopped by the police—on da way

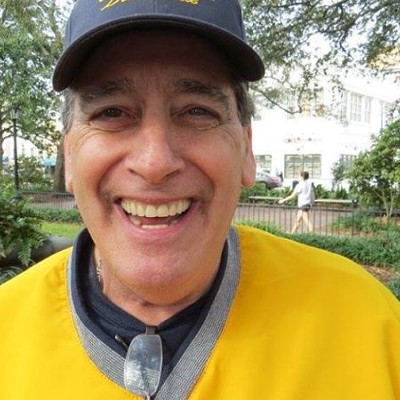

Five minutes later, local rapper Bugg Blow slides sheepishly into the booth with another apology. “I guess my car windows are tinted too dark.”

“Do you get pulled over a lot?” I ask.

“About four times a week,” he shrugs and orders a lemonade.

“Driving while black?” I joke clumsily to break the ice wall I forged in my snipey text.

He laughs. “Yeah, pretty much.”

I invited Bugg to lunch after I saw some of his astute posts about the killing of 12 year-old Keith Passmore. As a young black man, he’d wondered if the fact that Passmore was white affected how his death was reported. In his comments, Bugg asserted that Passmore was shot in a drug deal gone bad, but the media’s presentation of him as a freckle-faced innocent persisted in a way that it never would have if he’d been black.

Bugg defended his position calmly amongst the finger pointers and the know-it-alls. While there has been no confirmation of Passmore’s involvement in drugs, I appreciated Bugg’s tone: He wasn’t accusatory, just thoughtful, applying the kind of courtesy and courage that every Facebook troll ought to emulate.

With the embers of Ferguson still aglow and Savannah’s new police Chief Jack Lumpkin calling in the Georgia State Patrol to help deal with all these shot-up children, online civil discourse has had it rough lately. So much of the conversation has been revolving—and some might say devolving—around race, specifically on the depiction and perception of young, black men.

I’ve been in this business long enough to know that everyone has a story, and no one can be reduced to a stereotype if you listen.

But as empathetic as I believe myself to be, the fact is that I am not young, black or a man. And though I enjoy friendly acquaintance with some lovely young black men, I don’t ask them about being young black men because that would be weird and rude.

Bugg Blow, however, seemed like he wanted an opportunity to clarify what it’s like to be one young black man in Savannah, perhaps the kind easily stereotyped.

I didn’t think hearing his story could change the way we handle our crime crisis and our criminals. But talking over a plate of fried shrimp didn’t seem like a bad way to start. So I forgave him for being late.

Dressed in gray pants and pink and purple kicks, he introduces himself as 23 years old, a hiphop artist with three songs in heavy rotation on E93 and managed by DJ Mike Fresh.

“The radio don’t pay, but the shows do,” explains Bugg, ticking off a roster of recent gigs in Glenville, Jacksonville, Statesboro and Claxton. “It’s enough money to keep me out of trouble.”

But he matter-of-factly offers that this is a fairly new development. Raised on West 53rd Street by a single father who kept his kids fed by running low-grade check scams, Bugg (he didn’t want to divulge his real name) dropped out of Savannah High and eased right into the local illegal economy with the help of an uncle who’s now doing 15 years for homicide.

“In Savannah, there aren’t any gangs. It’s not like you think. It’s just a bunch of kids who’ve grown up together. At 15, I was living the life, selling weed, robbing people, toting guns—doing the same thing that little guy was doing,” he says, referring to Passmore, whose Facebook page showed a photo of the 12 year-old with a gun in his waistband before being taken down last week. He compares that to the killing of his friend Tre Walker in 2007, who was shot in the head walking home from school and vilified in the media as a thug.

Bugg says he doesn’t know who killed Keith Passmore but understands the kid’s ambition, invoking the term “street struck.”

“You’re a kid and you see the people pulling up in your neighborhood with the nice cars, and that’s what’s going to get the girls, that’s what’s going to get you the nice outfits. That’s what that kid was, street struck.”

It’s a pretty common condition in Bugg’s neighborhood. He says he’s not justifying any crimes, but he wants me to appreciate that when you need money to live and there’s a chance to sell drugs, you take it.

Or you don’t. I point out there are other, legal ways to make money.

“Like what? Get a job for minimum wage at McDonalds?” he wonders. “You can but that don’t support you.”

Since drugs appear to be at the crux of it all, I ask him if he thinks things would change if weed were legalized.

“I think it would make things worse. If they legalized weed, people would have to do something else to get by. Now they’d have to sell guns.”

We talk a bit about how deeply rooted the dysfunction is and how “everyone” knew former police chief and recent convicted felon Willie Lovett helped along the cycle.

Bugg is also a dad and speaks proudly of raising his 15 month-old daughter. He doubts that anyone will ever come forward to help solve the murder of 2 year-old Kiki Smalls, shot while sleeping, because even with promises of anonymity from the police, the fear of retribution reigns.

“Everyone is involved, and no one wants it to come back on them,” sighs Bugg.

He touches on the culture of silence on his track “Heaven and Hell”: Rest in peace Tre/ Rest in peace Tyrell/Before I snitch I’d rather slit my wrists and burn in hell.

Halfway through our conversation, a tall, broad-shouldered black man sits in the booth behind Bugg and whispers in his ear.

“Who’s that?”

“He’s with me,” says Bugg.

“Is he, like, your bodyguard?” I ask.

“More like a life coach,” says the man, who introduces himself as Jay. “I keep him on right track, make sure he’s not saying anything dumb.”

“How’my doing?” grins Bugg.

“Great,” I say. “Pretty good,” agrees Jay.

After a little cajoling, Jay joins us. He’s 26, softspoken and back in Savannah after graduating from college. He’d like to become a physician’s assistant, but that means more tuition money, which he doesn’t have.

“There’s not much out here for educated men and women in Savannah,” says Jay. “You’re a young black man and you come back home after going to school, what is there? There are people trying.”

I nod, tentatively offering that many Americans, regardless of race, have the experience that persistence and hard work just aren’t enough. After all, Breaking Bad was about a middle-aged white guy.

“I think people want to help,” I tell them. “What do you think would help?”

Bugg thinks for a moment. “Depends on what your goal is. Do you want to stop crime? Or do you want to help? If you’re trying to stop crime, you’re going to start a war. Because you’re trying to stop how people are making a living.”

Jay thinks raising the minimum wage would provide some incentive. “Crime happens because people need money. Better opportunities would mean less reason to participate in criminal activity.”

I agree. We riff for a while on that, and I ask these two gents what they believe are the obstacles to their success. Despite that we began by talking about racial biases, Bugg doesn’t think that’s the real problem, and maybe his point all along is that while young black men may be unfairly represented, everyone is susceptible to a life of crime.

“I don’t think its racism,” he muses. “I don’t think it’s about color. I think it’s about your level of life, the bracket you’re in. That’s very hard to change.”

Jay nods in agreement.

Our shrimp is cold and the lunch hour has long past. It seems like a good time to give up our booth and get on with life: Bugg Blow has shows lined up and a new mix tape coming out in January. I’m rooting for Jay to figure out the financial aid maze for his next degree. I thank them for the opportunity to ask them a bunch of rude questions.

Though we haven’t solved a damn thing, I also feel like a little more space has been scraped out for me to understand the complicated little city where I live.

With my hand on my heart, I pledge to keep listening. cs